_small.jpg)

Jenkins

is a former employee of the

Illinois Terminal Railroad and

founder and current president of

the Illinois Traction Society.

Jenkins is also the author of a

magnificent book on the Illinois

Terminal Railroad called "The

Illinois Terminal Railroad: The

Road of Personalized Services."

Jenkins' interest in

railroading, the Illinois

Terminal in particular, began in

childhood in his hometown of

Springfield. As a child he was

fascinated by the trains passing

close to his house -- so

intrigued that he would sit on

the rails waiting for the next

train to come along.

A friendly and concerned

Illinois Terminal Railroad

policeman took him under his

wing to ensure his safety.

Later, with the retirement of

his mentor just as Jenkins

graduated from high school, he

took over his friend's job with

the railroad. Jenkins spent 40

years as a railroad policeman

with the Illinois Terminal and

its follow-on companies. Upon

retirement, he undertook to tell

the story of the IT, some of

which concerned the city of

Lincoln.

In the late 19th century,

electric streetcars were

becoming common in the United

States. Lincoln had an extensive

system. Trolleys trundled all

over Lincoln, even going as far

west as the Chautauqua grounds,

currently Memorial Park. The

system ran in Lincoln from 1891

until 1928, when improved

streets and the growing use of

personal automobiles made the

streetcar line unprofitable.

In 1901, a Danville

entrepreneur named William

McKinley had a vision of what

the United States would become,

a vision that saw the increased

use of electricity to make the

lives of ordinary Americans

better. He bought his first

electric generating power plant

in 1901 in Danville.

Of course, a power plant

requires fuel, and the fuel of

choice in the early 20th century

was coal. The closest coal mine

to Danville was south of the

city.

Roads being what they were at

the time, transporting coal from

the mine to Danville was

difficult. McKinley came up with

the idea of building an electric

railroad from his power plant to

the coal mine. Many of the

miners were Danville residents,

so the train carried the miners

south to the mine and the coal

north to his power plant.

McKinley was not satisfied

with owning one power plant, but

began to amass plants in many

cities in central Illinois. He

was ushering in the modern age

of electricity to the homes and

businesses of the area. As with

most imaginative businessmen, he

saw the potential of the small

electric railroad he had created

in Danville and decided to

expand it to the west, initially

connecting Danville and

Champaign, then Decatur.

A few other like-minded men

had created small electric

railroads in central Illinois,

but they were for the most part

unsuccessful. McKinley began

buying these poorly run lines

and linking them together. It

can safely be said that he was

an organizational genius who

could look into the future and

predict what central Illinois

needed to grow, thus expanding

his own enterprises.

Eventually, McKinley's

railroad empire, called the

Illinois Traction System, would

link Danville, Champaign,

Decatur, Springfield, Peoria and

Lincoln to East St. Louis and

finally St. Louis. This electric

railroad became known as the

interurban.

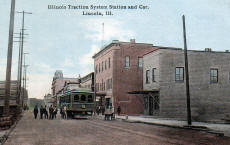

The interurban tracks on the

line from Peoria to Springfield

passed through Lincoln, right

down the middle of Chicago

Street, entering Lincoln from

the north and curving south

where Chicago Street ended at

the Stetson China factory.

The original interurban depot

still stands on South Chicago

Street -- a block building

standing by itself just north of

Baker Masonry. Back in the day,

the station stood next to the

Commercial Hotel, one of the

premier lodging businesses in

Lincoln at the time.

By 1908, 26 interurban trains

a day passed through Lincoln

from 5:30 a.m. to 11:30 p.m.

They took residents at a stately

25 mph to Peoria and Springfield

and points south. Roads were

abysmal at the time, so these

one- and two-car passenger

trains drawing power from an

overhead electric line were a

convenient and efficient means

to travel.

While the ITS tracks ran

parallel in some places to the

much larger Chicago & Alton

Railroad -- later to become the

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio -- the

interurban offered service that

the steam-powered passenger

trains could not.

The ITS prided itself on

personalized service, letting

passengers off at the tiny towns

such as Broadwell and Elkhart

along its right of way.

Richard Martin, a Logan

County resident and farmer,

remembers riding the interurban

from his home in Broadwell to

Lincoln. The trains would even

stop in the country to pick up

lone passengers needing a ride

from their farm into Lincoln.

Lincoln resident Bill

"Carlos" Gobleman remembers

boarding the interurban in

Lincoln with his shotgun, paying

35 cents and riding to Broadwell.

"I would then walk back to

Lincoln along the railroad and

hunt," he said.

Willard Emmons recalls his

father and sister riding the

interurban from Lincoln to

Peoria for their jobs during the

1940s. His father worked at

Caterpillar, and his sister

worked at a bag factory. They

traveled to Peoria early in the

week, stayed in an apartment

during the week, then traveled

home to Lincoln at the end of

the workweek.

[to

top of second column] |

The Illinois Traction System

became the Illinois Terminal

Railroad in the 1920s.

Jenkins related how McKinley

was not satisfied with just

carrying passengers on his

interurban. He offered same-day

package delivery service between

towns on his line. He also

initiated a small freight

service to increase the utility

of his railroad. The main

commodities carried were grain

and gravel.

McKinley's decision to begin

a freight service proved to be

prophetic.

McKinley began buying grain

elevators to integrate into his

growing central Illinois empire.

Bus service was also added when

roads were improved enough to

allow it.

In addition to providing

transportation and freight

service to Lincoln residents,

Jenkins related how the IT

brought entertainment to town.

Lincoln was on the vaudeville

circuit in the early 20th

century. When a vaudeville

troupe ended their evening show

in Peoria, they would tear down

and put their sets on the

electric railroad with the

performers to ride to Lincoln

for the next day's performance

at either the Grand or Lincoln

Theater.

As the years passed, the

interurban had increasing

competition from the expanding

use of the automobile, made

possible by the improvement in

intercity roads -- think Route

66 and other highways. By the

1930s, daily passenger train

service in Lincoln from the

Illinois Terminal dropped to 16

times a day.

The company tried to fight

back by increasing the luxury of

the passenger cars and

developing innovative services

such as lounge cars and air

conditioning.

The ITS was also the first

electric railroad in the world

to offer sleeping car service. A

passenger could board the

interurban in Lincoln in the

evening, enjoy a night's sleep

onboard and be in St. Louis the

next morning after crossing the

Mississippi River on the

McKinley Bridge, built by

William McKinley's personal

fortune.

But it was not enough.

After World War II, with the

increase in cars and decent

roads and the introduction of

more efficient diesel railroad

locomotives, the electric

passenger railroad in central

Illinois was doomed. Even with

the introduction of the fast and

luxurious Streamlines in the

late 1940s, McKinley's passenger

trains declined rapidly until

interurban passenger service in

Lincoln ended on June 11, 1955.

Lincoln railroading

enthusiast Paul Hines has the

distinction of being the last

passenger to step off the last

passenger interurban in Lincoln.

With the addition of a small

freight service early in the

20th century, the Illinois

Terminal burgeoned. Freight took

over from the passenger service

when the passenger trains ended

their service in the 1950s. For

many years after, the IT freight

trains chugged down Chicago

Street, pulled by the

distinctive green and yellow

diesel engines.

After 1962, the freight

service moved from Chicago

Street to the Illinois Central

tracks on the east side of

Lincoln. All that remained on

Chicago Street were the rails,

with the street now given over

entirely to cars.

The rails on Chicago Street

are now gone, but two remnants

of the era of electric passenger

service remain in Lincoln. The

aforementioned passenger depot

still stands, and a brick

electric substation is hidden

away on the southwest end of

Chicago Street, on property

owned by the Logan County

Highway Department.

There is also a combination

interurban depot and substation

at Union, nine miles north of

Lincoln.

For those who want to

experience a ride on the

interurban, a visit to the

Illinois Railway Museum is a

must. The museum has several

examples of interurban trains

that run. The museum is located

in the community of Union that

is west of Chicago. Note that it

is not the Union north of

Lincoln.

Dale Jenkins' lecture on

electric passenger rail service

in Lincoln is one of an ongoing

series of programs presented by

the Logan County Genealogical &

Historical Society at their

monthly meetings. The

organization is based at 114 N.

Chicago St. in Lincoln. Check

the website at

www.logancoil-genhist.org

for upcoming events at the

research center.

More information on the

Illinois Traction Society is

available at

www.illinoistractionsociety.org.

The Illinois Railway Museum's

website is at

www.irm.org.

[By CURT FOX]

|